August 2013 - In Search of the Western Sea

Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de la Vérendrye is remembered for his dreams as well as his discoveries.

Vérendrye was born at Three Rivers, Canada, on Nov. 17, 1685. In 1731, Vérendrye was authorized by the French Royal Court to travel from Montreal toward Winnipeg in order to establish trading posts, create alliances with the American Indians, organize the fur trade, and, most importantly, to discover a route to the Western Sea. The Western Sea was thought to occupy a large part of Midwest North America. In finding it, a person would have discovered a short cut to the Pacific Ocean and the Orient.

Vérendrye, his four sons and his nephew, Christope Dufrost de La Jemerais, were the first white men to travel from the east into the vast interior of the Canadian northwest. They opened the country west and south of Lake Superior to the French fur trade. They established a string of forts or trading posts that extended west from Rainy Lake, located on the Ontario/Minnesota border. Vérendrye was the first known white man to establish a post at the future site of Winnipeg and to journey into what is now North Dakota.

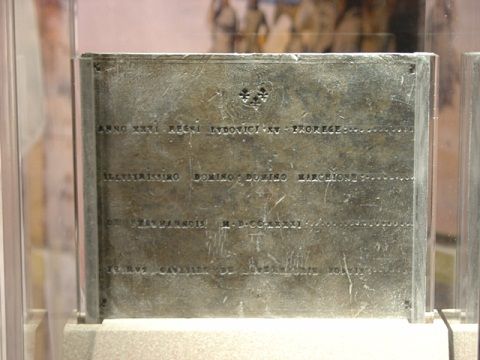

In 1742, Vérendrye’s sons Louis-Joseph and Francois, with a small company of men, traveled southwest from Canada to seek the Western Sea. They penetrated further into the heartland of North America than any previous known European explorers. Louis-Joseph buried a lead plate that his father had given him on a knoll near the Missouri River on March 30, 1743. This plaque bore the arms and the inscription of the king of France. The plate lay undisturbed for 170 years, until it was unearthed on a bluff in Fort Pierre by a group of teenagers. The plate made the short trip across the Missouri River and is one of the treasured artifacts in the museum of the South Dakota State Historical Society, located in the Cultural Heritage Center in Pierre. The site in Fort Pierre where the plate was found is a National Historic Landmark.

During the years he devoted himself to the search for the Western Sea, the explorer often found himself without supplies or money. In the fall of 1735, the convoy which was to resupply the forts Vérendrye had established failed to arrive. His nephew, La Jemerais, fell gravely ill from what some scholars have attributed to an inadequate diet and died. In June 1736, Verendrye sent his oldest son, Jean-Baptiste; a Jesuit missionary named Father Aulneau and 19 Frenchmen to get supplies. All were massacred by the Sioux on an island in Lake of the Woods.

“I lost my son, the Reverend Father and all my Frenchmen, a loss I shall regret all my life,” Vérendrye wrote in a memoir.

In the French royal court, Vérendrye was accused of inefficiency and profiting from the fur trade. He was humiliated when he was not promoted to the rank of captain and resigned.

“Contrary to what people think, my personal wealth has never been my principal motivation. My children and I have made many sacrifices in the service of His Majesty and for the good of the colony, and the advantages which can result from this will soon enough be known,” Vérendrye wrote.

Vérendrye received from the French court the rank of captain in 1747 and was asked to resume the search for the Western Sea. He was preparing for another journey when he died in December 1749. France’s highest decoration, the Cross of Saint-Louis, was bestowed on Vérendrye just before his death.

Vérendrye’s dream of finding the Western Sea could not have come to fruition, as the Western Sea does not exist. His passion for a cause, his always being ready to start over with eagerness and enthusiasm, and his hope as well as his discoveries are reasons why Vérendrye has a place in western history.

Vérendrye’s name still lives on. A wildlife reserve in Quebec, a park in Ontario, and a museum and historic site in Fort Pierre are among the places that bear the name of Vérendrye.

This moment in South Dakota history is provided by the South Dakota Historical Society Foundation, the nonprofit fundraising partner of the South Dakota State Historical Society. Find us on the web at sdhsf.org. Contact us at info@sdhsf.org to submit a story idea.