February 2015 - A Lifetime of Caring and Sharing

“No trip was too long or sufferer too poor to keep Dr. Jarvis from those who needed her service.”

Those words by her daughter Annette summed up the life of Abbie Ann Jarvis.

In 1898, Jarvis became the first woman licensed to practice medicine in South Dakota.

“She would be out all night on a doctor call and come home in the morning when the birds were singing. She’d be real happy, even though she’d lost a night’s sleep,” said Irene Cordts of Faulkton in a telephone interview. Now 103, Cordts was one of the many babies Jarvis delivered.

Jarvis, her husband Matthew and their two sons arrived in Redfield in 1880. Three years later, she and her family left Redfield to homestead.

The family moved to Faulkton in in 1888. They sold their homestead in 1890 and Matthew started a drugstore in Faulkton. Jarvis’ father, Samuel Hall, was a doctor in Faulkton.

About 1892, Jarvis took her 8- and 6-year-old daughters with her to Chicago where she began a four-year medical course at the Woman’s Medical College of Northwestern University. Her two sons remained in Faulkton with their father. In an article in the Faulkton Record, Helen Bottum wrote how Jarvis would go to bed early and wake up at 3 a.m. to study.

In the summer, Jarvis and her daughters would return to Faulkton.

Jarvis’ education was interrupted at the end of three years, when she left college to care for her ill mother. When her mother died in 1897, Jarvis and her daughters returned to Chicago and Jarvis resumed studying medicine. She graduated fourth in her class of 24 in 1898.

Jarvis, about 44 years old at the time, returned to Faulkton and started practicing medicine.

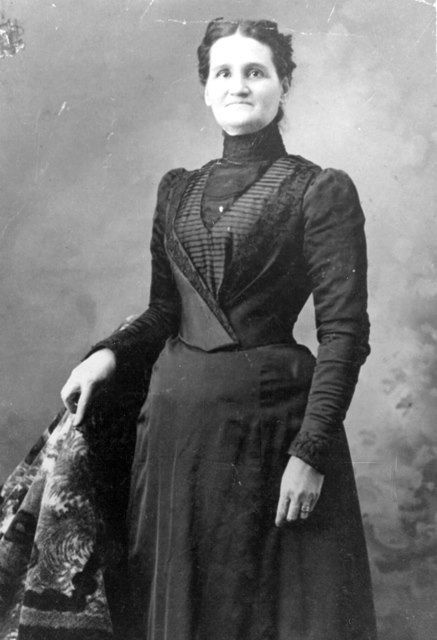

“She was a tall handsome woman with curling dark hair and snapping brown eyes,” Bottum wrote. “Her professional costume was a black dress and a big white starched apron. She carried the traditional black bag. As she opened the door she would call out cheerfully, ‘How art thou?’ Her face would be shining with friendliness and concern. Someone said, ‘Just a glimpse of Dr. Jarvis’ white apron makes me feel better.’”

There were immediate demands for Jarvis’ services, according to Bottum. Initially, she traveled by her horse, Lady Bug, and buggy. Later, she traveled by a car driven by a daughter or others.

Roads were prairie trails, farms were few and far between, nights could be starry or “pitch black” and the weather could be windy, rainy, snowy or scorching. She once sought shelter from a cloudburst by driving behind a haystack and waiting until morning. She arrived at the house soaked to the skin and bedraggled, but in time to deliver a boy.

“Frightened women on lonely farms waited for her Little Lady Bug and buggy and had perfect confidence that she would come, and she did,” Bottum wrote. “Women in childbirth had reason to bless her. At that time babies were not born in sterilized hospitals but in humble little homes where the boiler on the cook stove furnished the hot water and there was no sanitation.”

In 1915, Jarvis took a six-week post-graduate course at the Abbott Hospital in Minneapolis. She specialized in women’s and children’s diseases, according to an article written by Cordts. Some of the children diseases during the time of Jarvis’ practice were scarlet fever, typhoid fever, croup, whooping cough, diphtheria, pneumonia, spinal meningitis, pneumonia and inflammatory rheumatism. Some common afflictions of adults were stroke, typhoid fever, cancer, influenza and heart failure. Horse-related injuries from kicks and runaways were common.

Jarvis’ dream of a hospital in Faulkton came true in 1915 with the opening of Providence Hospital.

Jarvis and her husband experienced tragedy as well as blessings. A son, Matthew, died in an accident in 1905 and a daughter, Lucretia, died two years later of tuberculosis. Another daughter, Maggie Belle, died in infancy.

Jarvis was involved in the community as well as her medical practice. She was a worthy member of the Eastern Star, taught Sunday school and was active in the Methodist Episcopal Church.

“She was kind, loving, helpful. She was just all the good things you can think of,” Cordts said.

Jarvis practiced medicine almost until her death from cancer on May 2, 1931, at the age of 76.

Faulkton and South Dakota honored the pioneer physician in many ways after her death. She was featured in a “Dakota Images” article in “South Dakota History,” the quarterly journal of the South Dakota State Historical Society; inducted into the South Dakota Hall of Fame; honored as “Woman of Yesteryear” by the Resource Center for Women of Aberdeen; and chosen for inclusion in “The Argus Leader South Dakota 99,” which honored 99 people who had most influenced the state in its first 99 years. Jarvis was portrayed by Marilyn Peters of Britton at programs throughout South Dakota, was selected as the subject of a special postal cancellation during Faulkton’s observance of the state’s centennial in 1989, and was the topic of a South Dakota State Centennial history writing contest paper by Cordts.

This moment in South Dakota history is provided by the South Dakota Historical Society Foundation, the nonprofit fundraising partner of the South Dakota State Historical Society. Find us on the web at www.sdhsf.org. Contact us at info@sdhsf.org to submit a story idea.