November 2020-Badger Clark: Cowboy Poet and Jailbird

Badger Clark probably hoped to find adventure, money and romance in Cuba. What awaited him instead was a prison cell.

South Dakota’s first poet laureate (a title not yet bestowed upon him at the time) was among a group of people who left the country in December 1903 to colonize Cuba.

Colonizing plans fell through, and the 21-year-old Clark was the only would-be colonizer who remained in Cuba after April 1904. He went to work for plantation owner Augustin Rodriguez.

Clark’s sense of humor was evident when, in 1906, he wrote about his experiences in Cuba. They were published in the Summer 1977 volume of “South Dakota History,” the quarterly journal of the South Dakota State Historical Society.

Rodriguez often quarreled with two of his neighbors, father and son Emilio and Enrique Barretto. The feud escalated one morning when Enrique threatened Rodriguez with a machete. Rodriguez fired his gun at Enrique and wounded him. Rodriguez and Clark soon found themselves in a six-by-10 foot jail cell.

Brought before the court, Clark was informed that he had deliberately, feloniously, and with malice aforethought fired at Enrique at a distance of 10 feet and missed.

“I immediately put in an indignant plea of not guilty,” Clark wrote.

Clark and Rodriguez were told that they could get “libertad provisional” if they would put up the sum of $300 apiece for bail.

After three days in jail, the two men were transferred to the provincial penitentiary, where they were separated and forbidden to communicate.

“I reached the low water mark of despondency that afternoon when the steel doors of the big prison closed behind us,” Clark wrote.

“I was thrust into a large cell with seventeen convicts. When I sized up these fellow sufferers of mine, I was if possible sicker than before … Not one of them spoke English and most of them spoke a very poor dialect of Spanish ….”

His cell had an informal government with a prisoner called the “Presidente” in charge.

“The daily program at the prison was so simple and easy to learn that after a few days it became almost monotonous. We arose at six in the morning. At six thirty a man came to the door of the cell carrying a five-gallon kerosene can full of coffee. Under the supervision of the Presidente we filed out and one at a time filled our tin cups with the thick brown mixture. This coffee was all we were given for our breakfast, but we generally eked it out with a piece of bread saved from dinner the day before. This bread kept us busy because it had to be eaten slowly on account of the number of ants it contained.

“After breakfast we were left to our own devices for awhile … As for me I lay in my bed and smoked innumerable cigarettes while I read stories from some old American magazines. Had it not been for these magazines, I might have gone crazy for want of something to take my mind off my troubles.

“At ten o’clock in the morning we ate our ‘almuerzo’ the first real meal of the day. Almuerzo consisted principally of soup. It was a thick soup and was probably highly nourishing, if grease and nourishment are synonymous.

“At four o’clock in the afternoon the comida or heavy meal of the day was served. The principal dish at this meal was the soup of the morning, only the strictly soup part had been drained off leaving the solids in the form of a kind of ‘boiled dinner.’ This was rather (more) palatable than the soup and the fact that they gave us a small allowance of bread, fruit, and coffee made it quite a feast.”

The interval between comida and bedtime was generally the noisiest of the day, as this was the time the prisoners did most of their singing.

“At nine o’clock the guards would extinguish the lamps and the Presidente would command silence … This was the hardest time of day for me. I could not sleep before midnight, and so I would lie and think unpleasant thoughts and listen to the prison bell as it struck the halves and quarters.

“Two weeks dragged on before I procured my release. Despite my troubles I thrived rather than pined, and the only possible damage my health suffered during my confinement was from smoking too much.”

Rodriguez put up bail for Clark. Clark felt he had to stay in Cuba to keep Rodriguez from losing the $300. Clark was acquitted at his trial on Jan. 31, 1905.

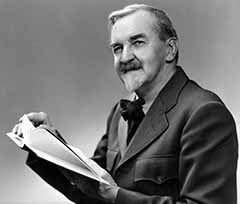

Clark returned to the United States, where he became known as a cowboy poet. He was named South Dakota’s poet laureate on Dec. 24, 1937, a title he held until his death in 1957.

This moment in South Dakota history is provided by the South Dakota Historical Society Foundation, the nonprofit fundraising partner of the South Dakota State Historical Society at the Cultural Heritage Center in Pierre. Find us on the web at www.sdhsf.org. Contact us at info@sdhsf.org to submit a story idea.