September 2013 - The South Dakota Name Game: Who Named What

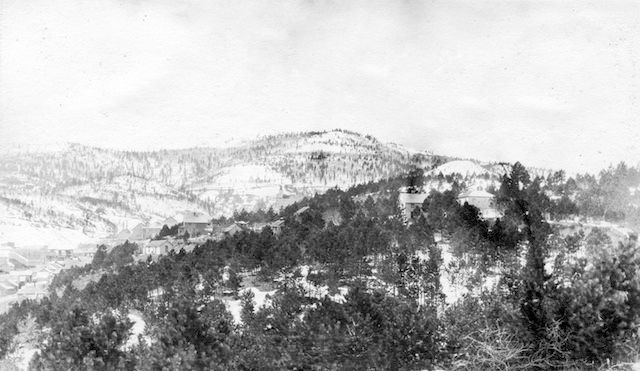

Terry Peak

Boxes and lumber marked “J.D. Hilger, Pierre, east of Fort Pierre” were unloaded from a river boat onto the east bank of the Missouri River in May of 1880. John Hilger, his brother Anson and Anson’s wife and son were waiting to retrieve the items.

That was the explanation Anson Hilger gave for how he named Pierre, according to Harold H. Schuler’s A Bridge Apart.

Pioneer merchants such as Hilger, explorers, military officers, settlers, railroad officials and more have all left their mark on South Dakota by the names they gave to its lakes, towns and mountains.

In 1838, 2nd Lt. John C. Frémont accompanied French-born naturalist Joseph N. Nicollet as Nicollet mapped the area between the Upper Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Frémont charted several lakes in northeastern South Dakota. He named Lake Benton after his future father-in-law and powerful U.S. Sen. Thomas Hart Benton; Lake Preston after South Carolina Sen. William Campbell Preston; and Lake Poinsett after his friend and benefactor Joel Poinsett. Frémont christened another lake Abert after his superior, U.S. Army Col. J.J. Abert. This body of water later became known as Lake Albert.

When Gen. George Armstrong Custer and the 7th Cavalry entered the Black Hills in 1874, they were journeying into a place unknown to non-Indians. En route from Fort Abraham Lincoln near present-day Mandan, N.D., to the Black Hills, Indian scouts led expedition members to a cave that was an important spiritual place to them. Custer named the cave after Capt. William A. Ludlow, the chief engineer for the Department of Dakota. Custer also named a stream in what is now Pennington County Castle Creek because the high cliffs between which it flows reminded him of castles. He presumably conferred the name Gold Run upon a small tributary of Castle Creek.

While standing on the most elevated portion of the Black Hills, Ludlow named two prominent peaks for Custer and Gen. Alfred Terry.

Ludlow and Nicolett both retained many place names given by American Indians when making maps.

The town of Wasta received its name when state historian Doane Robinson selected the Lakota word for “good” for the Pennington County community. Robinson also named the town of Tolstoy in honor of the Russian writer.

Charles Prior worked in the Minneapolis office of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad, deciding where new railroad tracks would go and where towns would be located along the railroad. He is said to have named a community in Brown County Aberdeen because his boss, Alexander Mitchell, came from Aberdeen, Scotland. Prior named another town site Virgil due to his admiration of the Greek poet. He named Alpena for a town in Michigan, Ipswich for his own birthplace in England, Bath and Bristol for cities in England and Woonsocket for a town in Rhode Island. He also named Wilmot, probably after Judge Wilmot W. Brookings. A railway official named the town of Bradley out of gratitude to E.R. Bradley, who saved his life when Bradley intervened in a fight between the official and laborers. Other railroad officials named Alcester, Amherst, Canistota, Junius, Java, Huron, Hitchcock, Renner, Trent, Worthing, Frederick, Mystic, Orient and other towns.

Settlers sometimes made themselves feel more “at home” by naming their new town after the one they had left. Edward Tilton and other settlers named Hartford for their home town in Connecticut. Czech settlers named Tabor for a town in Bohemia. William Van Epps named Madison because the nearby lakes reminded him of the Wisconsin city.

Other settlers honored people by naming a place after them. Dr. O. Richmond named Tyndall for John Tyndall, a British scientist. Lily was named by the town’s first postmaster, Ross Parks, after his sister, Lily. Holabird owes its name to Henry Wicker, superintendent of the North Western Railroad. He gave his bride’s family name to the new town.

As for the state’s most well-known geographic feature, one story goes that an eastern attorney was in the Black Hills in the early 1880s when he asked his guide the name of a granite peak. The guide, William Challis, said that the mountain did not have a name before, but would now bear the lawyer’s name. Another story states that the attorney joked that he had visited the Black Hills so many times that he had earned the right to have the mountain named after him.

The attorney’s name was Charles Rushmore, and whatever the story, the United States Board of Geographic Names officially recognized the name Mount Rushmore in 1930.

Rushmore’s name, like that of John Tyndall, Thomas Hart Benton and so many others, lives on in South Dakota’s geographic names.

In 2009, the South Dakota Legislature created the S.D. Board on Geographic Names to replace certain geographic place names considered offensive. The board has established a public process and works with the U.S. Board on Geographic Names. For more information, see www.sdbgn.sd.gov.

This moment in South Dakota history is provided by the South Dakota Historical Society Foundation, the nonprofit fundraising partner of the South Dakota State Historical Society. Find us on the web at www.sdhsf.org. Contact us at info@sdhsf.org to submit a story idea.